How the Corruption Perceptions Index Misrepresents Corruption in Latin America

Latin American countries continued to score poorly on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI), published on January 30, but the index presents a flawed picture of corruption dynamics in the region.

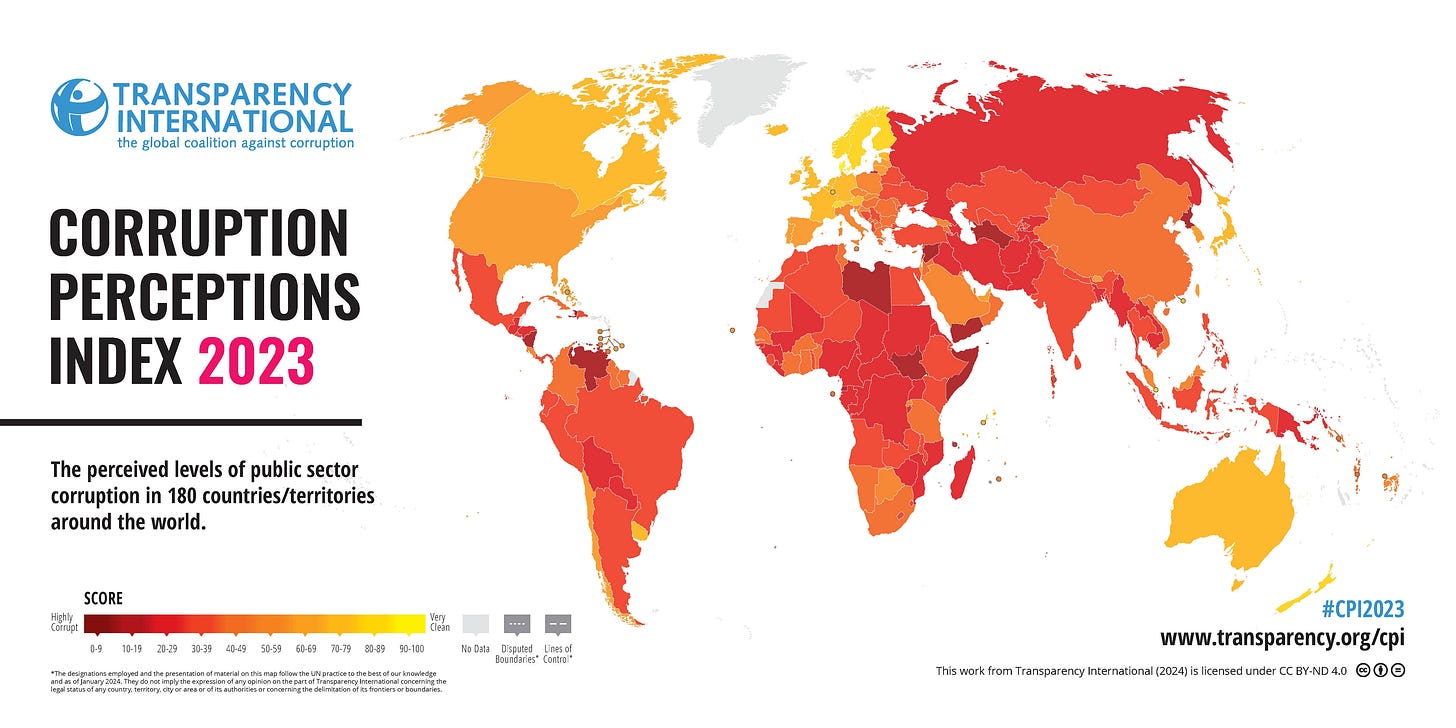

The CPI, which has become a staple in corruption reporting, ranks countries between 0 and 100 based on perceived levels of public sector corruption with 0 representing extreme corruption and 100 no corruption at all.

Perceptions of corruption remained stagnant overall with Latin America’s average score moving down 0.3 points from 41.6 to 41.3, according to the report. As always, the average hid considerable diversity. Uruguay, the region’s consistent winner, topped the tables with a score of 73. Venezuela did less well, sliding to an all-time low of 13

The index managed to irk a number of governments. In a strongly worded communique, Honduras’ Department for Transparency rejected the findings describing them as “irresponsible.” In Brazil, outgoing minister of Justice Flavio Dino went further suggesting, wrongly, that Brazil’s poor score was the result of political motivations. "Anyone who uses the fight against corruption as a political banner is just as corrupt as the corrupt," he said in a thinly veiled reference to the index.

While the CPI continues to get generous media coverage and is effective at drawing attention to the issue, there are some reasons to take the report with a large pinch of salt.

1. It Measures Perceptions, Not Actual Corruption

Transparency International itself is clear that the CPI measures perceptions of corruption, not corruption itself. This nuance, however, often gets lost when media outlets report on the index, many of which treat the index as if it were a definitive measure of actual corruption.

What’s more, the index only picks up perceptions of a specific type of corruption, tending to focus on the perceived likelihood of being asked for a bribe by a public official while completely ignoring corruption in the private sector and money laundering.

For example, Uruguay (73) continued its unrivaled streak as being perceived to be the least corrupt country in Latin America, its score never dipping below 70. The country has low crime rates and public services are efficient.

But perceptions can belie reality. Money laundering cases in Uruguay linked to drug traffickers have doubled in the last five years, raising concerns that organized criminal groups are quietly turning Uruguay into a hotspot for corruption and illicit financial flows.

2. It Ignores the International Aspects of Corruption

While the CPI ranks corruption between countries, the index ignores that much corrupt activity is international in scope and can rarely be pinned to a single geographic location.

For example, in 2018, Miami prosecutors brought charges against a Uruguayan banker who was accused of laundering $1.2 bn of funds stolen by employees of Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), the Venezuelan state-owned oil firm. The prosecutors alleged that the cash was then funneled through a Puerto Rican bank and used to purchase luxury property in Florida, though the charges were recently dropped.

Oliver Bullough, an author and corruption expert, told The Honduran Journal that “Corruption, like any business, is globalized.” He emphasized that kleptocracy was largely dependent on shifting stolen funds across international boundaries to obscure their providence and obstruct the efforts of law enforcement.

To be sure, it is not clear if the case had any impact on Transparency International’s CPI calculations. If it did, however, only the CPI of Venezuela would have been affected as this is where public funds first went missing.

“Could Venezuelan (kleptocrats) be corrupt without Miami? Well, yes, they could, but they couldn't be anything like as corrupt because it wouldn't be possible for them to get away with the scams if they didn't have somewhere to spend the money,” said Bullough.

3. It Ignores the Role of Countries that Facilitate Corruption

Of the 32 Latin American countries measured by the CPI in 2023, just 10 achieved scores above 50. The star performers consistently include financially secretive jurisdictions including St Lucia (55), Dominica (56), and St Vincent and the Grenadines (60).

In these countries, rules surrounding what individuals need to disclose before purchasing assets or creating shell companies are lax and transparency requirements are low. The setup benefits wealthy elites and provides a source of income for small island economies, but also presents opportunities for large-scale corrupt activity by making it easier for kleptocrats to hide ill-gotten gains, something which is altogether ignored by the CPI index.

On a global level, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and the United States also presented squeaky-clean CPI scores despite doing some of the most damage with their financial secrecy regulations, according to data from the Tax Justice Network.

“If you don't talk about the people who provide the corruption services that allow people to be corrupt, then you're missing half of the story,” said Bullough, who went on to describe the CPI’s misrepresentation of corruption as ‘deeply harmful’.

“The fragment that is told (by the CPI) is always a poor country inhabited by people with dark skin .… And the countries that are ranked highly are always in the global north … The result is objectively racist and that's a real problem.”